Last month's excursion At The Edge Of Town might have pulled in a whole brace of disparate and far-reaching memories, ranging from extended vibe-outs and recording sessions out in Ramona to twilight writing marathons on the shores of Lake Cuyamaca, and even long, late-afternoon drives through Borrego Springs in the dead of winter, but the real catalyst that set the whole thing into motion was Jean-Luc Ponty’s Cosmic Messenger, an album I've been rocking relentlessly for the past six weeks, cruising around the Heights and chilling out in Palm Grove to its moody, windswept soundscapes.

That record's a travelogue in its own right and it got me thinking about how I crossed paths with Ponty’s music in the first place, all those years ago. Revisiting it also brought to mind a few interesting connections that I've often wondered about (connections I've never seen mentioned anywhere else, truth be told), so it seemed as good a time as any to put them all down in one place. As such, this isn't so much a piece about the great jazz violinist's music itself — although that does get a look-in — as it is a map of possible routes leading in and out of his musical world: a collection of “Pathways to Ponty”, if you will.

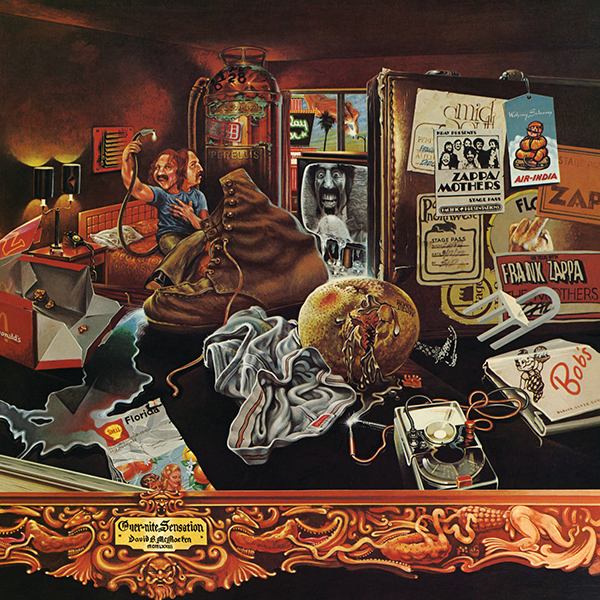

Back in the day, if you were coming from rock music, chances are you'd have been hipped to Ponty through his tenure in Frank Zappa’s early '70s band, a period when he cropped up on records like Hot Rats and Over-Nite Sensation, records that more often than not still get singled out as highlights in Zappa’s vast discography. At the time, Ponty even recorded an entire solo album devoted to Frank’s music — King Kong: Jean-Luc Ponty Plays The Music Of Frank Zappa — which featured none other than Zappa himself stepping in on lead guitar for “How Would You Like To Have A Head Like That”.

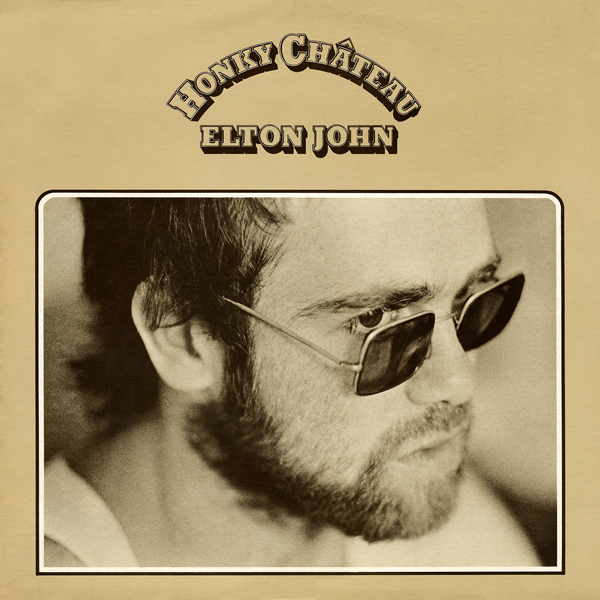

Around the same time, Ponty also guested on Elton John’s Honky Château LP (for my money, one of his best albums), contributing electric violin to the New Orleans-inflected piano pop of “Amy” and “Mellow”’s rootsy downbeat chill. This would've brought his sound to an entirely different strata of the pop landscape at a time when Elton’s star was undeniably on the rise. My Dad was actually aware of Jean-Luc Ponty because of his playing on Honky Château, since — ever the Elton die hard — he'd pored over the album's liner notes growing up. When I finally did come home with my first Ponty record, his response was a moment of recognition, followed by the simple remark: “oh yeah, I think he played on Honky Château.”

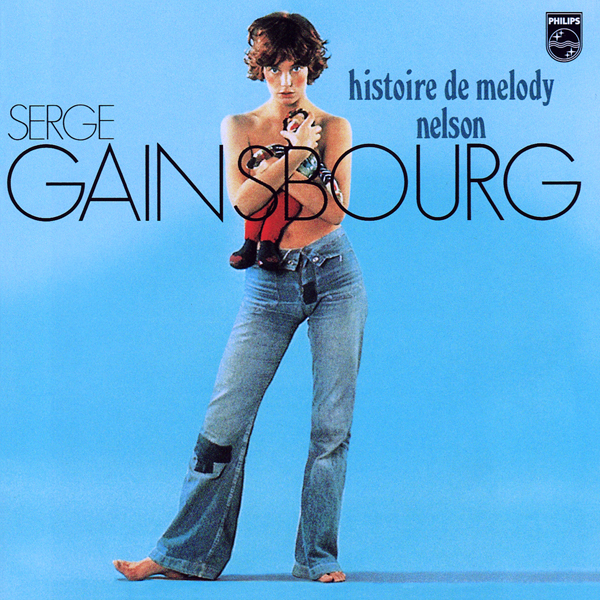

Tangentially, I'm always surprised that Ponty’s contemporaneous appearance on Serge Gainsbourg’s Histoire De Melody Nelson — where he contributes a searing electric violin solo to “En Melody” — isn't more widely noted. In the 21st century, an era where this album has become something of a stone tablet, an undeniable classic (partially thanks to the same post-'90s “breaks” aesthetic that brought a whole new generation to the music of David Axelrod), the album works as another potential portal into Ponty’s music, especially when you first hear the unmistakable strains of his violin rising from the mix, making you want to hear more.

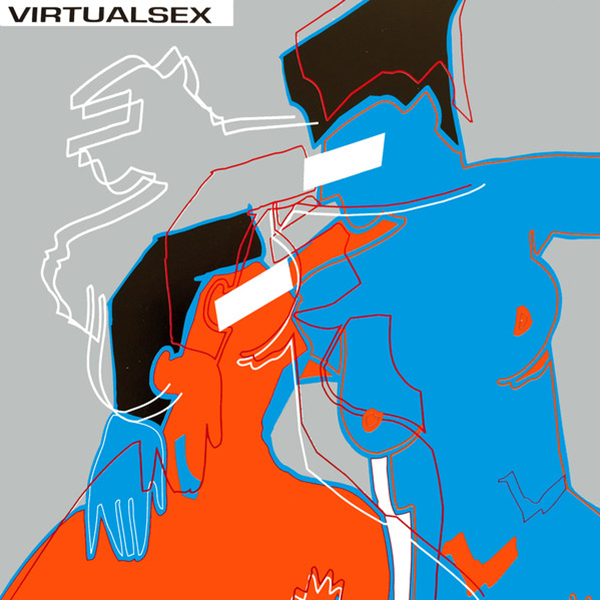

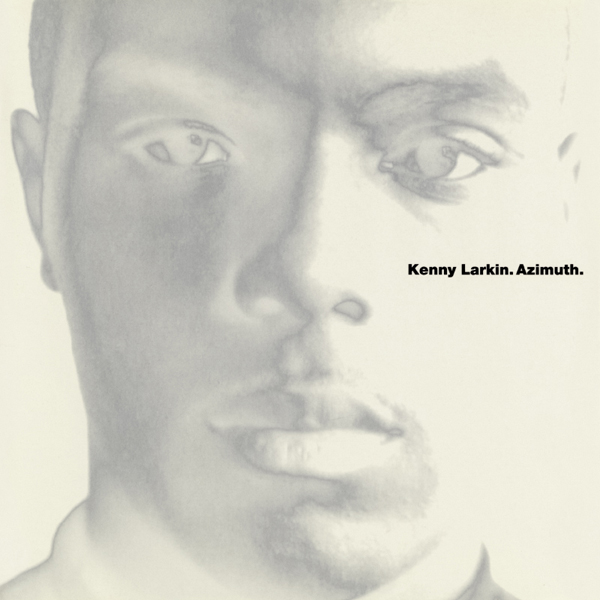

For my part, I came to the Ponty’s music not through rock or French pop or even jazz proper, but — as with so many other things — by way of electronic music.[1] Since so much of the genre's key music was already pretty hard to track down by the late nineties, you'd often end up reading about it long before ever getting a chance to hear it.[2] I remember reading about Kenny Larkin’s “Tedra” — a song that originally factored into Buzz’s epochal Virtualsex compilation — in Techno: The Rough Guide, where Tim Barr compared its melodic construction to Jean-Luc Ponty.[3] Naturally, that put Ponty firmly on my list of musicians to check out.

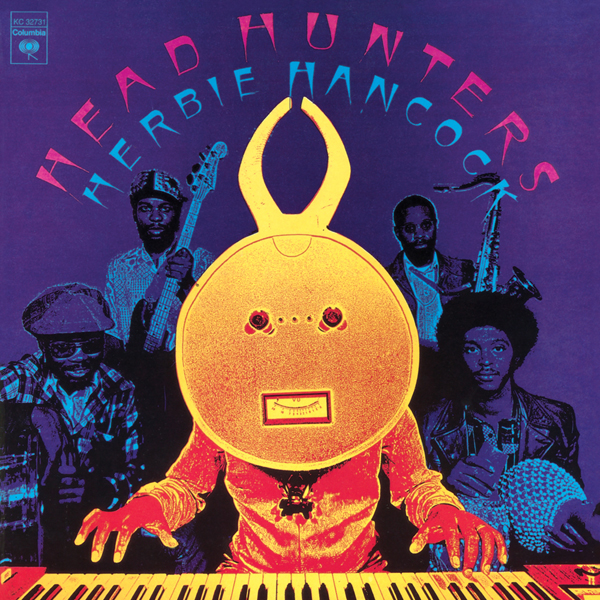

You see, this was the rare case where I'd actually had a chance to hear the song in question fairly easily. Although I was still some years away from getting my hands on the Virtualsex compilation, “Tedra” was also included on Azimuth, Kenny Larkin’s debut album from the following year.[4] I loved the track's plangent, glistening synth shapes, its drifting piano melody, and the way those low key electro beats pushed the track's gentle refrain ever forward. It was a relatively early incursion of post-techno dance music into the amorphous realm of tech jazz, and the mirror image of Herbie Hancock’s pioneering work emerging on the other side, from jazz proper (Head Hunters already a crucial record for me at the time — the first jazz record I ever owned, in fact).

So when the chance came to go one step further and check out Jean-Luc Ponty’s music, I was more than happy to take the plunge. At the time, I worked shelving books at the San Diego Public Library, and in my capacity as library aide (low man on the totem pole), I'd also help set up the periodic book sales they'd host. These sales were used to shift old books, either pulled from circulation or donated to the library by patrons, raising a little extra money for the branch in the process. Since this was back when everyone was shedding their old record collections — most likely clearing out their attics and garages to make way for the future — there was a lot of great music coming in all the time too. As a thank you for helping out with the set up, I'd usually get to grab a couple books and/or records at a heavy discount.[5]

So one day, I go to grab a crate of records that I'm hauling over to the book sale, and what should I see but the dapper image of Jean-Luc Ponty staring back at me from the cover of Enigmatic Ocean! Without a moment's hesitation, I hooked it out into my bag of goodies and — for the modest price of 25 cents — got to take it home for an after-work listening session, where its kinetic melange of widescreen jazz fusion wound up being my introduction to the man's music (it was also one of the very first jazz records I ever owned, alongside the aforementioned Head Hunters, Sun Ra’s Cosmic Tones For Mental Therapy, and Miles Davis’ On The Corner). Little did I know that it also happened to be Ponty’s most commercially successful album, reaching #1 in the Billboard Jazz Album charts and even #35 in the Pop Album charts (the '70s really were a different time!).

|

|

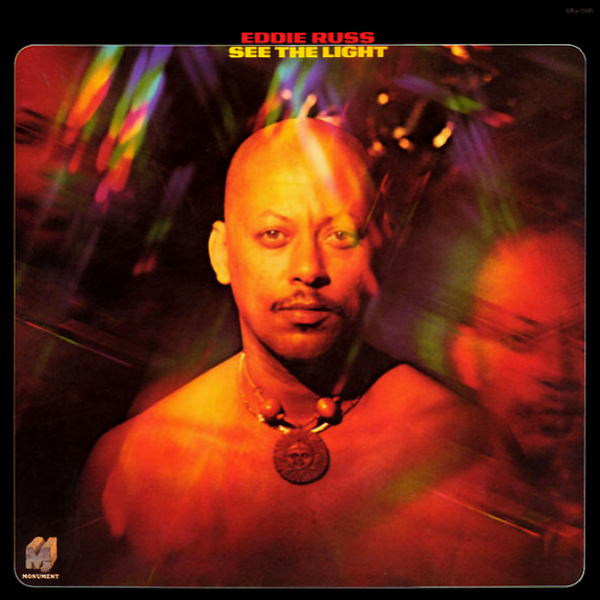

From there, I was hooked. Not much later, I picked up his 1978 follow-up Cosmic Messenger on CD. I was immediately sold on the sleeve (how could I not be!?), which turned out to perfectly match the music enclosed within; but the title caught my eye too, making me flash on Stacey Pullen’s Kosmic Messenger project. At the time, I figured it was just coincidence, but now I'm not so sure... the Kosmic Messenger alias may have been an outlet for the Detroit techno icon's most dancefloor-oriented sides, but his Silent Phase output shares striking similarities with some of Ponty’s later, more electro-tinged material. There's a definite tenor to this particular corner of Pullen’s discography that's always struck me as a spiritual descendant of '70s jazz records like Julian Priester’s Love, Love, Eddie Russ’ See The Light, and Johnny Hammond’s Gears.[6]

This aspect of Pullen’s music really came to the fore with the Todayisthetomorrowyouwerepromisedyesterday LP. Released in 2001, it's his final album to date. Not too widely celebrated at the time — in fact, it almost seemed to fall through the cracks[7] — but where I'm coming from it's a stone cold classic of bent-circuit electronic jazz, stacked with 21st century broken beat, digital jazz funk, a touch of drum 'n bass, and loads of undiluted techno soul. Case in point is “Vertigo” — the primary single from the album — which set cinematic strings, vintage sun-glazed synths and wailing, wordless vocals against a skewed, effect-drenched rhythm matrix that recalls peak-era Rhythim Is Rhythim. Truth be told, it's not a million miles removed from the sort of thing one might encounter on a Jean-Luc Ponty record.

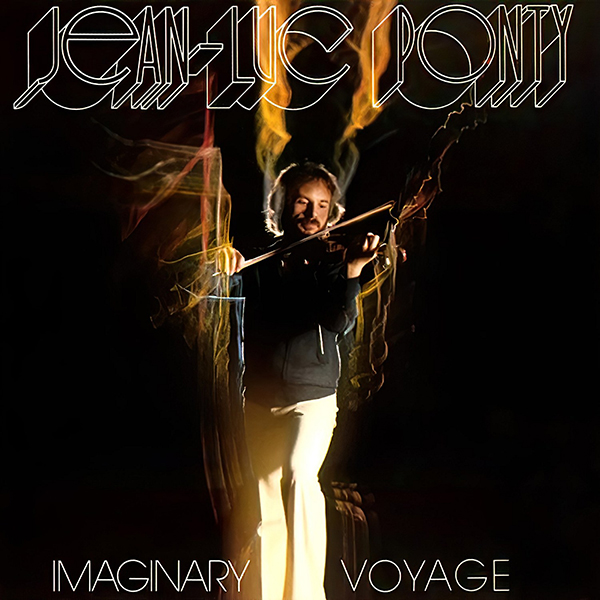

Take a song like “The Gardens Of Babylon” — from the album Imaginary Voyage — where Ponty’s electric violin plays off the rolling eddies of Mark Craney and Tom Fowler’s drum and bass bedrock, Allan Zavod’s liquid Rhodes flowing through the spaces in between, while Daryl Stuermer plucks out the fragile counterpoint on acoustic guitar. Subtract the 20 year gulf in technology and “Vertigo” is practically saying the same thing![8] Speaking more broadly, there's a drifting, ethereal quality to Ponty’s work that's very much “in tune” with the continuum of near-ambient electronic music running from Klaus Schulze and Tangerine Dream all the way through The Orb and Wolfgang Voigt, which continues right up to the present day. On the surface, it's most obvious when he eschews beats altogether — as in the extended glissando trip “Wandering On The Milky Way” — but also in his propensity for long, flowing suites (such as Imaginary Voyage’s four-part title track),[9] instantly bringing to mind fellow Frenchman and all-around electronica don Jean-Michel Jarre.

For me, this sort of thing dovetailed quite naturally with some of the parallel explorations I'd recently been making into the world of progressive rock, which — surprise, surprise — was spurred on by another techno institution: The Future Sound Of London. At the time, FSOL had been doing their psychedelia-tinged The Mello Hippo Disco Show transmissions for a couple years, while the slowly gestating follow-up to their Dead Cities LP (which would become Amorphous Androgynous’ The Isness) was rumored to be heavily indebted to prog. In retrospect, they'd been moving in that direction ever since Lifeforms,[10] the liner notes even mentioning that they'd pulled “guitar textures” from Robert Fripp and “sound bytes” from Ozric Tentacles (once again marking both names out for further exploration!).

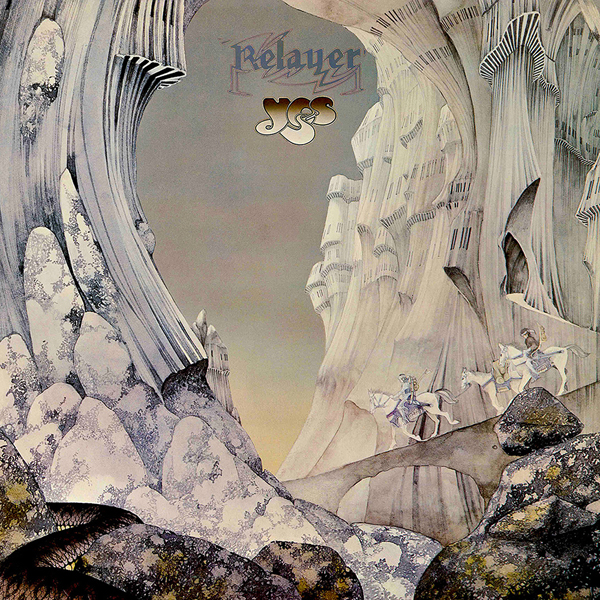

Accordingly, records like Ozric Tentacles’ Sliding Gliding Worlds and Fripp & Eno’s (No Pussyfooting) were some of the first prog discs that I checked out — just after Yes’ Close To The Edge and Relayer[11] — and Ponty’s records were very much at home in this company. In fact, I've often thought the track “Cosmic Messenger” managed to strike a rather similar mood to the Ozrics early records — capturing that same sense of downbeat widescreen grandeur, delivered with a crisp, three-dimensional, almost dub-inflected production aesthetic — while the album’s more lightspeed fusion passages are certainly fellow travelers with the atypical prog-into-jazz stylings of Relayer. There's a real “Non-Stop Home”-style proto-junglist sensation to fiery fusion workouts like “Egocentric Molecules” and “Don't Let The World Pass You By”, not just in the careening tempos but also the way their spectral synths are set adrift in Timeless ambience against the all-encompassing fury of that dynamite rhythm section.

As often as not, I'm reminded of the great spaced-out jungle LPs from fifteen years later, records like 4 Hero’s Parallel Universe and the Jacob's Optical Stairway album, A Guy Called Gerald’s Black Secret Technology, Goldie’s Timeless, and LTJ Bukem’s Logical Progression. With a tune like “Don't Let The World Pass You By”, there's a real sense that Ponty is driving his band to play together so tightly that their sounds all melt into a single rhythmic flow: liquid jazz and breakbeat science moving at the speed of light. Add those gorgeous synths into the equation — streaming like rays of sunlight through the jungle canopy — and it's hard to shake the feeling that you really are listening to the music of the future.

|

|

Indeed, the synths on “Don't Let The World Pass You By” really are something special. So special, in fact, that they were lifted wholesale by none other than The Future Sound Of London thirteen years later! The first time I heard the song's opening synth refrain it practically floored me, since I immediately recognized it from Candese’s “You Took My Love (Earth Mix)”, a song I must have already heard a thousand times by then. FSOL deftly wove Zavod’s synth line into the fabric of their track, letting its shimmering descent spool out with a gravity all its own, hiding within the framework of one of their four-dimensional breakbeat workouts like diamonds scattered across the nighttime sky. First heard on the Earthbeat compilation — a disc I'd played non-stop for the preceding couple years — I eventually tracked down the original 12" on Debut[12] some time later. However, I'll always think of the tune as a highlight of the indispensable Earthbeat compilation,[13] an absolute classic packed with some of the duo's finest early tracks and singular sounds (some of which, it turns out, came courtesy of Jean-Luc Ponty himself!).

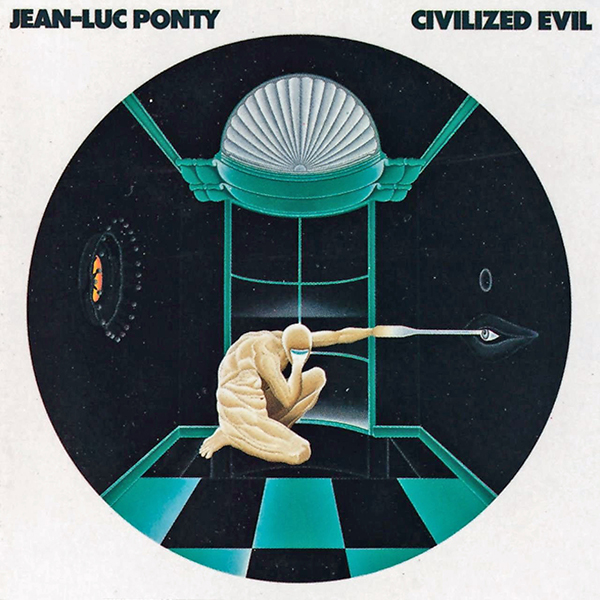

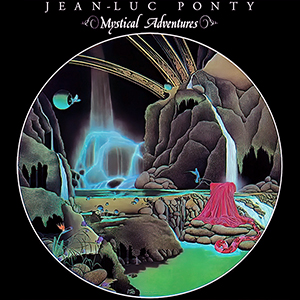

And when it came to synths, Jean-Luc Ponty was just getting started. As he moved into the 1980s, Ponty — who'd already been producing his own albums since 1975’s Upon The Wings Of Music — was gradually drawn deeper into the mechanics of the studio and started to embrace the one-man-band approach to making music, which would later reach its apotheosis in 1984 with Open Mind (more on this later). The transition could start to be felt as early as 1980’s Civilized Evil — at times sounding like a fusion analogue to The Alan Parsons Project’s I Robot or Landscape’s synth/prog/pop extravaganza From The Tea-Rooms Of Mars... To The Hell-Holes Of Uranus — but the real turning point was Mystical Adventures, which bridged the gap between the cosmic fusion of Enigmatic Ocean and his sequencer-driven tech jazz sound of the mid-eighties (don't worry, I'm still getting to that!). Coming on like Cosmic Messenger’s kid brother (just check that sleeve),[14] it maintained the rhythmic propulsion of a live drummer (in this case, Rayford Griffin) even as the floodgates opened for an array of colorful synthesized sounds to seep further into the mix (once again matching the sleeve perfectly).

|

|

In fact, the synths here tend to approach the reflective feel of lush techno and house music to come, particularly things like Larry Heard’s Sceneries Not Songs, Volume One and Silent Phase’s (The Theory Of) Silent Phase. Appropriately enough, there's another potential Stacey Pullen connection right there in the title, which is shared by his contribution to the Virtualsex compilation, Bango’s “Mystical Adventures (Mystic Mix)”. Like “Tedra”, the song later crops up on another record (in a slightly different version), this time as the b-side to Bango’s second record, Sphinx/Mystical Adventure. “Mystical Adventure” itself is a minor masterpiece of lopsided techno soul, and a real precursor to the brittle melodicism of his coming Silent Phase material (and yes, oddly reminiscent of Ponty’s too). These Bango records were some of Pullen’s earliest releases (if I'm not mistaken, the first, self-titled Bango EP was actually his debut), coming out on Derrick May’s Transmat subsidiary Fragile, a label I practically worshiped back in the day and one that really deserves a dedicated piece in its own right.

There was a real aquatic, washed-out quality to much of the label's output that sits comfortably in this conversation, with an undeniable jazz-inflected charge running through the entire catalog, even as it pulled in disparate strands ranging from Reese’s hard techno conceptual missive Inside-Out and the clangorous minimalism of Man Made’s Space Wreck/Industry to Choice’s longform proto-trance epic Acid Eiffel and the ambient post-junglism of Dyonis’ New Day. The label's penultimate release was even a straight up tech jazz romp in the form of John Arnold’s Sparkle, a not-too distant cousin to Recloose’s early EPs.[15] Beyond that, the classics come thick and fast: the first BFC record (the one with “Galaxy”) was the second 12" put out by Fragile, while records like Aqua Dance by A Scorpion's Dream and Complex’s Midi Merge (produced by Dutch techno dons Steve Rachmad and Orlando Voorn, respectively) were unleashed a few years later, and the awesome post-techno space music of Digital Justice’s Theme From: It's All Gone Pearshaped hitting a few years later still, standing tall at the precipice of the 21st century to offer a brave glimpse of the possibilities available therein.[16]

All of which squares remarkably well with something like 1984’s Open Mind (I promised you I'd get to it!), which represents Ponty’s vision at its most self-consciously electronic. Like Herbie Hancock’s Future Shock trilogy, this is tech jazz avant la lettre, prefiguring things like UR’s Nation 2 Nation and Innerzone Orchestra’s Bug In The Bass Bin by five or six years, it makes do with the tools of its time in exemplary fashion. Despite figures like Chick Corea occasionally manning the synths and George Benson playing guitar on a couple tracks, it's basically a one man show, featuring sequencers in abstract motion beneath Ponty’s live soloing on electric violin. Appropriately enough, I'm reminded (once again) of Jarre’s contemporary music, this time meeting late-period Weather Report somewhere in the middle for a late-night jam session atop the Sears Tower.

Perhaps more surprisingly, there's quite a bit going on here that plays like some strange premonition of Derrick May’s peak-era Rhythim Is Rhythim output, with Ponty’s sharp electric violin shapes paralleling the icy strings of May’s Ensoniq Mirage, and even the staccato programmed percussion mirrors May’s notoriously treble-heavy rhythm matrix. Right off the bat, the title track threads the needle between “Strings Of The Strings Of Life” and “Beyond The Dance (Cult Mix)”,[17] while gentle moments like “Solitude”, “Modern Times Blues”, and “Intuition” bring to mind late-period Mayday treasures like “"Rest"” and “Kao-Tic Harmony”. Something like “Icon (Montage Mix)” (originally rubbing shoulders with “Tedra” on the Virtualsex compilation) even manages to split the difference between both sides of the coin. Maybe nothing on Open Mind packs quite the same down-n-dirty punch as Rhythim Is Rhythim’s skyline symphonies, but there's an expansiveness to Ponty’s vision of electronic music that skirts the outer edges of May’s dense sonic architecture, occasionally even hinting at his unparalleled sense of drama.

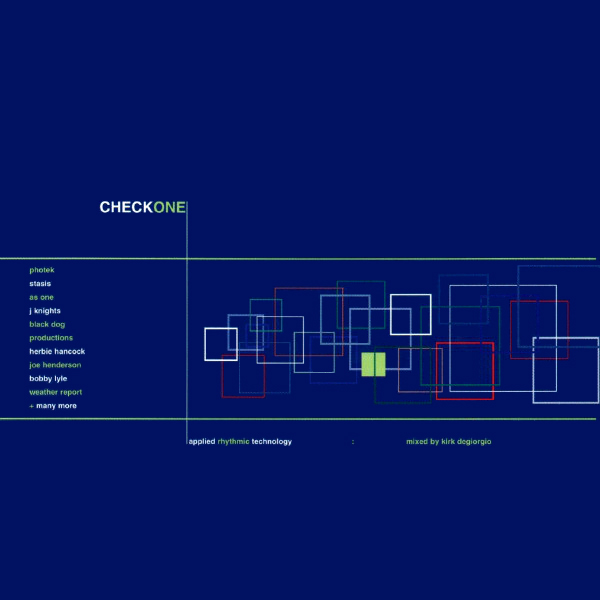

In fact, there's a lot of subsequent activity by Ponty’s spiritual descendants that also exists at this axis, figures that would have been as strongly influenced by Derrick May’s music as they were the explorations of the earlier jazz pioneers. I'm talking about prototypical tech jazz figures like Dan Curtin, Kirk Degiorgio, and Ian O'Brien, producers who'd further Ponty’s explorations at the interface of jazz and technology with records like Pregenesis, In With Their Arps, And Moogs, And Jazz And Things, and A History Of Things To Come. The missing link between UR’s “Jupiter Jazz” and Innerzone Orchestra’s Programmed, they were a key part of the slipstream that carried the music into the 21st century,[18] paradoxically by opening up techno's headlong future rush to the infinite possibilities hinted at by the past. Much the same way that one goes back to their roots to rediscover fundamentals that might have fallen by the wayside over time, it squared the circle between techno's furiously programmed present and the funky improvisation of days gone by. At its best, the effect was the musical equivalent of opening a wormhole into the distant past to rediscover the secrets of the pyramids (or in this case, the stone tablets of the 1970s and beyond).

Looking past the grooves of their own (often great) records, these figures made invaluable contributions in seeding this secret knowledge back into the culture. In the early days of the internet, Kirk Degiorgio curated the Op-art Hall Of Fame, laying out a treasure trove of great music at the axis of soul, jazz, and electronic music. It was an invaluable resource to someone like me who was just starting to work their way backwards from the music of the present. Mr. Kirk and Ian O'Brien even collaborated on a trilogy of compilations called The Soul Of Science, dusting off classic jazz and funk cuts like George Duke’s “North Beach”, Dunn Pearson Jr.’s “Groove On Down”, and Graham Central Station’s “'Tis Your Kind Of Music” to rub shoulders with new music by like-minded producers of the present (including Degiorgio and O'Brien themselves in various configurations).

At the time, I also remember soaking up O'Brien’s DJ sets on Groovetech (a sorely-missed online record shop from the early 21st century), where he'd cross vintage '70s jazz cuts from figures like Lonnie Liston Smith, Freddie Hubbard, and Ramsey Lewis with of-the-moment broken beat, house, techno, and electronic jazz by figures ranging far and wide, from Moodymann and Anthony Shakir to 4 Hero, Afronaught and even The Black Dog, sprinkling in choice vocal cuts by artists like Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Joni Mitchell and Flora Purim, and spiking it all with thoroughly unclassifiable oddities like Sluts'n'Strings & 909![19] It was a true glimpse into another world, an on-ramp to a superhighway where 4 Hero, Charles Stepney, Carl Craig, Tonto's Expanding Head Band, Roy Ayers, Jazzanova, Sun Ra, and Wayne Shorter were all shimmering nodes laid out in a vast, interconnected network of sonic possibilities.[20] I can't imagine discovering an album like Eddie Russ’ See The Light so early any other way.

If there was one record I can think of that served as the ground floor to the whole phenomenon, it must have been Kirk Degiorgio’s awesome Checkone mix, which pulled this trick first, crossing old '70s material like Herbie Hancock’s “Nobu”, Julian Priester’s “Prologue/Love, Love”, and Bobby Lyle’s “Inner Space” (coming on like the secret godfather to Psyche’s “Neurotic Behavior”) with the contemporary tech jazz of Photek’s “T'Raenon”, Jedi Knights’ “Solina (The Ascension)”, and Silent Phase’s “Meditive Fusion”. I remember an old interview Mr. Kirk did with Woebot,[21] who remarked that there was a decade-long gap between the old and new material (roughly spanning the years 1979-1992), and posited that something like Maze’s “Twilight” would have bridged the divide. Degiorgio said that he actually had considered “Twilight”, but ultimately decided it would've been too obvious since Goldie had just sampled it for a track around the same time. To bring it all back to old Jean-Luc, I remember thinking that some of the cuts from Open Mind — “Intuition” and “Modern Times Blues” in particular — would have been a perfect fit for that mix. and from right in the middle of that interzone decade.[22] Strangely enough, I don't remember Ponty’s music ever coming up in either O'Brien or Degiorgio’s mixes, even though it always seemed (to me, at least) to fit firmly within their particular corner of the greater musical neighborhood.

And that's really what this whole project boils down to tonight: sketching out a map of possible “Pathways to Ponty” (and some of them are even confirmed pathways!). There will be plenty that I've missed too... this is still just scratching the surface. For a man who managed to play with two of the “big three” fusion outfits (Mahavishnu Orchestra and Return To Forever) over the years, it would take a lot longer to cover it all. Even on his own records, you'll find jazz heavyweights ranging from Chick Corea and Patrice Rushen to Allan Holdsworth and fellow Zappa alumni George Duke playing along with his sweeping musical visions.

For me, each of these “Pathways to Ponty” are fascinating in their own right, since they all link up into a lattice of coincidence connecting so much of the music I love, from Detroit techno and the Earthbeat records to tech jazz, Serge Gainsbourg, and all sorts of other things in between. There's little I enjoy more than “connecting the dots” in cases like these, because it's the exact same way I moved from node to node in the pursuit of musical discovery in the first place. There's an undeniable thrill when you start to see the connections, nodes bouncing off each other to cast it all in a new light.

And yet, what gives the whole thing its meaning is the hub from which all these other spokes radiate, the node lying at the center of this particular conspiracy of sound (if that's not worthwhile, then who cares?). In this case, it's the music of Jean-Luc Ponty tying everything together, even as it stands firmly on its own merits. His is an utterly unique body of work in the world of jazz and beyond, well worth exploring if you're so inclined. No one else sounds remotely like him, and no one plays with sound in quite the same way he does, molding and shaping it into beguiling scenes and strange configurations.

If you're at all interested in fusion, you can't go wrong with the Imaginary Voyage/Enigmatic Ocean/Cosmic Messenger trilogy, while later records like Mystical Adventures and Open Mind would almost certainly appeal to those with a taste for the brittle end of electronic music. Taken together, they're like twin sides of the coin for a man who drove his band to play so tight they'd melt together into one, and then turned around and dove so deep into the studio — digitizing his sound so deftly and thoroughly in the process — that it paralleled the electronica of its day (and our present day too, truth be told). These records are the voyages of a true Cosmic Messenger.

Footnotes |

|

|---|---|

|

In truth, I worked my way back through the entirety of jazz this way, from Underworld to Juan Atkins to Herbie Hancock to Miles Davis to Charles Mingus to Duke Ellington. I'd been interested in jazz ever since I was a kid, but didn't know where to start. In the end, it was techno that opened the door into that whole world (like the man said, “Jazz Is The Teacher”). |

|

|

This just before P2P filesharing a la Napster really took off, and almost a decade before Youtube started to gain serious traction. |

|

|

Barr, Tim. Techno: The Rough Guide. Penguin, 2000. 190-191. Print. |

|

|

Since it came out on Warp Records, Azimuth was one of the easier Detroit techno discs to get ahold of in those days (I actually picked up my copy at Frys, of all places). |

|

|

I managed to accumulate Alvin Toffler’s entire Future Shock trilogy this way. |

|

|

In contrast, I'd always heard the Kosmic Messenger material — particularly traxx like “Eye 2 Eye” and “Freeky Deeky” — as picking up where Funkadelic’s The Electric Spanking Of War Babies left off. |

|

|

For whatever reason, it was only ever available as an expensive import, despite coming out on Astralwerks subsidiary Science — practically a major label! |

|

|

Pushing my luck now, there's even something of an affinity with Massive Attack’s Protection in evidence here (particularly instrumentals like “Weather Storm” and “Heat Miser”), specifically the way the piano in “The Gardens Of Babylon” settles into an errant sojourn across the lush, laidback soundscape, where liquid Fender Rhodes melts into Ponty’s wandering electric violin figure. |

|

|

Enigmatic Ocean has two of them: the four-part “Enigmatic Ocean” and the three-part “The Struggle Of The Turtle To The Sea”! |

|

|

In fact, they got a lot of stick at the time for their prog-ward tendencies from loads of contemporary critics still toeing the punk party line. I distinctly remember FSOL being unfavorably compared to Jean-Michel Jarre, Vangelis, and Tangerine Dream on more than one occasion... these days that would be a badge of honor! Just goes to show you how much the winds of fashion can change. |

|

|

Checking Yes first was an almost reflexive move, since my brother Brian must have played Highlights: The Very Best Of Yes a thousand times when we were growing up... it was practically part of our DNA by then! Besides, the name Yes has always been synonymous with progressive rock. |

|

|

Debut was a sub-label of Passion Records (home of the great Sun Palace record) that existed in parallel to Jumpin' & Pumpin', the primary outlet for Dougans & Cobain’s early output. The duo's records as Mental Cube also came out on Debut, including the awesome Chile Of The Bass Generation EP, my absolute favorite thing they ever did. |

|

|

Like Mr. Fingers’ Ammnesia, the Earthbeat compilation was one of those discs that seemed nearly impossible to find at the turn of the century, until filesharing swooped in to save the day. In both cases, I wound up making do with a burnt CD of MP3s downloaded off the web (thanks Audiogalaxy!) that I played obsessively for a long time before finally getting ahold of the genuine article many years later. |

|

|

The cover images for Cosmic Messenger, Civilized Evil, and Mystical Adventures were actually all conceived by Jean-Luc’s wife, Claudia Ponty, and painted by Daved Levitan. All three are great sleeves no doubt, and there's even something of a shared sensibility with the futurescapes later found in Abdul Haqq’s artwork on Detroit techno-era records like Intergalactic Beats, Orlando Voorn’s Divine Intervention, Relics: A Transmat Compilation, Dark Comedy’s Corbomite Maneuver, 313 Detroit, and Psyche/BFC’s Elements 1989-1990. |

|

|

In fact, Sparkle’s second track, “Universal Mind”, was an undeniable highlight of Carl Craig’s (Onsumothasheeat) DJ mix, where it appeared alongside Recloose’s “Landscaping”. |

|

|

Even Aril Brikha’s micro-house touchstone “Groove La Chord” made its first appearance on a Fragile 12". |

|

|

Pushing my luck even further, I'd argue that there's a bit of Ken Ishii circa Innerelements about “Open Mind”. |

|

|

Sure enough, there were a whole lot of others too: from the loose-limbed acid jazz of Max Brennan and the Holistic label to Jimi Tenor’s space age bachelor pad music and everything going on in Germany with Jazzanova and Compost Records, not to mention 4 Hero’s post-Parallel Universe transformation from ardkore renegades and jungle innovators into dons of the West London broken beat phenomenon.

However, it's the trio of Dan Curtin, Kirk Degiorgio, and Ian O'Brien whose music tends to hew closest to Jean-Luc Ponty’s later, more electronic records. |

|

|

This was one of Patrick Pulsinger and Erdem Tunakan’s many great projects to spring from their Vienna-based Cheap Records house of horrors, an utterly unique label that will definitely warrant a discussion of its own in the near future. I distinctly remember Ian O'Brien on the air — just after playing this record — saying something like “that was “Put Me On!”, from the album Carrera by Sluts'n'Strings & 909,” followed by a pregnant pause, and then remarking “Hmmm...” in a genuinely disapproving tone! Still cracks me up to this day... |

|

|

For me, it was a little like catching some forgotten '70s conspiracy thriller starring Steve McQueen, Bill Duke, Jennifer Warren, Jean-Louis Trintignant, William Conrad, and Vonetta McGee on TV — purely by chance — some late summer afternoon in the mid-nineties. |

|

|

Ingram, Matthew. The Big Book Of Woe. Hollow Earth, 2012. Clash of the Titans. Digital. |

|

|

While I'm at it, here's a few more that would've been great to slip into Checkone: Sun Palace’s “Rude Movements”, Wally Badarou’s “Chief Inspector (Vine Street)” and N.Y. House'n Authority’s “APT. 3B”. |

|