Over the course of Spoonie Gee, Terranova, and The Terminal Vibration protracted denouement — which really boiled down to an extended tribute to The Clash’s Sandinista! — a couple things occurred to me about that record and its eventual aftermath that hadn't before. The first was already outlined in the piece itself, namely that The Clash’s 1980 triple-LP was really the spiritual blueprint for the sort of sample-heavy beatbox excursions that would become Big Audio Dynamite’s calling card later in the decade, a sound and approach that would mutate into the dusted m.o. of the 1990s and records like Paul's Boutique, Odelay, and Paradise Don't Come Cheap.

The second, poetically enough, is that this whole nexus of dusted beatbox maneuvering turned out to be the very middle ground where Mick Jones and Joe Strummer would meet up again (sonically speaking) a decade and a half after the dissolution of The Clash. Strange to say, but I've never actually heard anyone make this connection before. In fact, critics would usually go on and on about how different the The Mescaleros and B.A.D. were from each other, contrasting Joe Strummer’s salt of the earth realism with the supposedly “dated” production palette employed by Mick Jones and co. I'd argue they weren't paying attention. By the turn of the century, it was as if the baton were passed from Jones to Strummer, their respective sounds converging to reap a sweet harvest of the fertile terrain they'd left in their wake all those years ago.

Allow me to explain...

Set your mind back to 1983, the year that Joe Strummer and Mick Jones first parted ways. In the immediate aftermath of Jones’ expulsion from The Clash, their paths couldn't have been more different: Strummer’s Cut The Crap version of the band returned to the fiery sound of old,[1] ultimately embarking on the acoustic Busking Tour in 1985, which would also turn out to be the band's defiant farewell. Mick Jones formed his own genre-bending beatbox crew Big Audio Dynamite,[2] which would go on to cut a singular path through the next decade in multiple incarnations. And yet when all was said and done, they both wound up the nineties in the hazy hangover of post-rave indie dance, plying a sound largely built on dusted post-hip hop beats and dub's heavy bottom end, albeit with a healthy dose of good old-fashioned power pop running through its veins.

Of course, you could have already found a precedent for all of this activity in the dynamic duo's 1986 detente on Big Audio Dynamite’s sophomore album, No. 10, Upping St.. After turning in a strong debut LP, This Is Big Audio Dynamite, Mick brought in old sparring partner Joe Strummer — then still smarting from The Clash’s untimely break up — to co-produce B.A.D.’s second effort.[3] Things quickly escalated from there, and Strummer wound up co-writing some of the album's strongest cuts, including “V. Thirteen” (a soaring power pop number in the vein of old Clash anthems like “I'm Not Down” and “Somebody Got Murdered”) and the pile-driving “Sightsee M.C.!”.

The latter cut provided the clearest outline of the path forward, taking the spirit of the debut’s beatbox rave up “BAD”[4] and amplifying it, adding an apocalyptic heaviness and ruffer bottom-end than anything on the debut. Coming on like a digitized sequel to “The Guns Of Brixton” — taken out for a top-heavy, slow-motion joyride on the London grid — “Sightsee M.C.!” features one of Mick Jones’ periodic quasi-raps[5] and toasting from Don Letts over crashing beats and Art Of Noise-style orchestral stabs. Those ancient, ominous strings roll out across it all like dark clouds brimming over with heavy rain, just waiting to fall like a hail of bullets onto the city below. It's ragga in all but name and an undeniable fellow traveler with the post-dancehall dubwise moves of Adrian Sherwood’s On-U Sound setup — particularly Tackhead’s industrial-strength big beat attack — a fact borne out by Paul "Groucho" Smykle’s dub deconstruction of the track on its 12" single,[6] which is a dead ringer for something off Mark Stewart + Maffia’s self-titled third album.

You can trace this comfort with such forms back to The Clash’s time in New York City during the Combat Rock sessions,[7] when Mick Jones was known to walk around town with a boombox on his shoulder, blaring the latest hip hop tapes like he was Radio Raheem. As strange a sight as that may have been at the time, it also meant that Jones was plugged in at the source when it really counted — at a time when he could soak up everything from hip hop and electro to early house and freestyle — long before the Second Summer Of Love was even a glimmer in the eye of merry old England. It's one of those seemingly inconsequential early details that wound up making all the difference once the kaleidoscopic rush of rave finally rolled around, since B.A.D. was more than ready to take it head on — and on its own terms — with no reservations and no half measures.

For all the evidence you need, check out Megatop Phoenix, the band's 1989 magnum opus. Infusing everything from Chicago house (a la Marshall Jefferson) and Derrick May-style Detroit techno to proto-junglism straight outta London (inna Shut Up And Dance stylee) and the wild Manchester free-for-all of A Guy Called Gerald and 808 State into music that couldn't be mistaken for any other band in the world, and then spiking it further with traces of New York freestyle, Marley Marl’s hip hop sampladelia and elements of the Minneapolis sound. It's a striking tour de force laid down like it were the most obvious idea in the world, by a crew jacked into the era's crucial currents and operating at the peak of their powers.

NO other rock band got this music at a deeper level so early in the game. Not Madchester upstarts like the The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, or The Charlatans UK. Not New Order, who were still largely reliant on 12" remixes from luminaries like Kevin Saunderson and Mike "Hitman" Wilson for their added dancefloor punch (no shame in that) and stuck with their trademark Balearic indie power pop sound for most of 1989’s Technique. Even Primal Scream needed to draft Andrew Weatherall behind the boards to make their ecstasy dreams come true on “Loaded” and Screamadelica, and by then it was already the nineties. Only A.R. Kane came close, with "I" (also released in 1989), particularly in offbeat club cuts like “A Love From Outer Space” and “Snow Joke”. And if you find yourself neck-and-neck with A.R. Kane in 1989 after going toe to to with Sex Pistols over a decade earlier... well, you're probably doing something right.[8]

Another less obvious part of Megatop’s greatness is the way its dancefloor moves have been filtered-down, deconstructed, and then rebuilt like some ramshackle Studebaker coupe (bringing to mind the Gila Monster Car from O.C. And Stiggs), delivered with the same sort of shambolic post punk spirit that you'd find in old records by Maximum Joy and A Certain Ratio. When I first heard the album — in the midst of the clean-cut precision of the tech house boom and the widescreen glamour of turn-of-the-century trance — it seemed like something of a liability, but in the intervening years it feels more and more like an unshakable strength (much like Carl Craig’s homespun productions on the early Psyche/BFC records), lending the whole LP a loose, off-the-cuff charm that was largely lacking in the locked-down pulse that defined much of the early 21st century dance landscape[9].

As if to prove the point, Jones doubled down on that shambolic charm over the next couple years with his second iteration of the band and its twin albums,[10] Kool-Aid and The Globe. The electroid Kraftwerk-meets-Moroder-isms of “Kool-Aid” are but window dressing for a laidback mid-tempo groove that picks up where “Medicine Show” and “Everybody Needs A Holiday” left off, bringing it on home to the '90s (where it belongs), it's a dusted affair through and through, playing like a dress rehearsal for Hot Chip’s Coming On Strong. Perhaps most striking of all is “In My Dreams”, the instrumental of which sounds for all the world like some downbeat smoker's delight escaped from Nightmares On Wax’s A Word Of Science: The 1st & Final Chapter.

It all reaches its dusted crescendo on The Globe, which splits the difference between a more literal, post-Madchester take on indie dance[11] and sampladelic hip hop, with an undeniably dusted hue cast on its most downbeat corridors. This record's version of “In My Dreams” sounds even better than the original — with a more blunted bottom end that puts it squarely in Mo Wax territory[12] — while the crawling tempos, cinematic sweep, and vocodered refrain in “When The Time Comes (Part 2)” sound more like The Detroit Escalator Co. than you'd expect.[13] In practice, the title track might be the most obvious example of all, essentially made up of samples from The Clash’s “Should I Stay Or Should I Go?”, its power chords and stiff beat the stomping ground for Jones to trade verses with an uncredited MC's raps.[14]

For his part, Strummer had been quietly turning out music of his own in the years since No. 10, Upping St.. My favorite of the bunch is undoubtedly this score for Alex Cox’s film Walker, which serves as an eerie precursor to the “invisible soundtrack” aesthetic that would inform large swathes of nineties music (alongside things like exotica and library records, for similar reasons). With its Morricone flourishes, folkloric touches and shades of traditionalism all shot through with a sun-glazed flavor, it prefigures not only the whole Tarantino/Rodriguez aural aesthetic but also large swathes of the dusted sound, particularly things like Beck’s Odelay, Deadweight, and Guero.[15]

Right off the bat, “Filibustero” hits you with the sort of low-slung Latin shuffle you'd find in proto-dusted tunes like Santana’s “Evil Ways” and Steely Dan’s “Do It Again”, a sound that gets carried into the nineties by the likes of Dangerman, Cake, and Beck. “Sandstorm” has all the epic bluster of a classic Morricone theme, while the record's shimmering, vivid sound occasionally brings to mind Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas soundtrack (particularly in its gentlest moments, like “Tropic Of Pico”). You even get a handful of affecting vocal cuts thrown into the bargain, songs like “Tropic Of No Return”, “Tennessee Rain”, and “The Unknown Immortal”, where Strummer establishes the whole rustic troubadour aspect of his persona, something he'd carry with him for the rest of his career.

There's a real “the guns cooled in the cellar” revolutionary spirit to the whole affair that picks up where The Clash’s “Gates Of The West” left off, even as Strummer’s whole approach here is Fourth World almost by default, bringing to mind later outfits like Up, Bustle & Out and the Nortec Collective. Add just a little breakbeat punch to tunes like “Omotepe” and “Nica Libre”, and they'd be right at home on a record like Light 'Em Up, Blow 'Em Out or Master Sessions 1: Rebel Radio a decade later. This is just the sort of record that a whole lot of blunted producers would have killed to have made in the late-nineties, fitting in perfectly with the slipstream of downbeat collage that came in dance music's wake (the fact that it was later reissued by Astralwerks bears this out).

After lying relatively low for most of the '90s, Joe Strummer emerged with a new band — The Mescaleros — releasing their debut album Rock Art And The X-Ray Style right at the end of the century. The timing couldn't have been more perfect, with their music existing at the axis of dusted's late-nineties flameout and the new wave concision of the early 21st century post punk revival. After a burst of radio static, the opening bars of “Tony Adams” unfold with punk reggae inflections and a low-slung hip hop beat,[16] and it's immediately clear that you're in for a treat. Just like everything else on the record, this music is quintessentially Joe Strummer, even as it's spiked with that fin de siècle post-everything touch, where all the ingredients get thrown into the blender and the chips are left to fall where they may.

The Mescaleros’ records also key into the sort of punk/rap/reggae mash up that bands like Sublime, 311, and Sugar Ray called their own in the '90s, even as Strummer reminds you who drew up those blueprints in the first place.[17] And things go deeper still: “Techno D-Day” could practically be a Black Grape song (rather appropriate considering that Strummer worked with them on the England's Irie single three years earlier). Black Grape’s squaring the circle between lumpen indie dance and post-hip hop dusted menagerie on It's Great When You're Straight...Yeah is actually a decent blueprint for whats going on here, served up with a side of beatnik eclecticism that brings to mind Damon Albarn’s globetrotting post-Blur trajectory. There's even echoes of Ultramarine and The Orb in the acid-drenched slow-motion skank of “Yalla, Yalla” and “Sandpaper Blues”’s infectious merger of cod-West African music and ambient house.[18]

Of course, there's still a healthy undercurrent of London Calling-style power pop to be found here (just check out “Forbidden City” and “Diggin The New”), while Strummer’s troubadour leanings really come into into their own. A track like “Road To Rock N' Roll”, with its collision of confessional folk and hip hop beats,[19] makes me wonder whether he'd been soaking up Everlast’s Whitey Ford Sings The Blues (Strummer well known to have always had his ear to the ground), while “X-Ray Style” manages to capture that mercurial essence of vintage Stones records like Sticky Fingers and Exile On Main St.. Just as Sun’s rockabilly was a timely collision of country music and the blues, much of the music that could conceivably be called “dusted” served up a merger of indie folk and hip hop, from The Beta Band and Beck’s acoustic roots all the way back to Basehead’s debut in 1991. There's a homespun, Basement Tapes sensibility to the album's most gentle moments that gives them a ramshackle, demo-like quality, undercutting the record's freewheeling beatbox futurism with a gutsy beating heart.

On the band's follow-up, Global A Go-Go, these varied ingredients all go into the cauldron and really get a chance to boil over into a singular fusion of beatnik beat music. With its rude skank and dubwise flavors, “Cool 'n' Out” picks up where “Tony Adams” left off, albeit with a more frenetic beatbox punch reminiscent of peak-era Renegade Soundwave, ultimately crashing into a crescendo of big beat feedback like The Sabres Of Paradise’s Wilmot being covered by a gang of unruly punks. With its marriage of Bollywood strings and highlife guitar lines played out over rolling breakbeats, “Bhindi Bhagee” sounds like something Cornershop might have cooked up if they went out and tried to make a Clash record circa When I Was Born for the 7th Time. Once again, there's a real parallel with Damon Albarn’s post-britpop beatnik world travels in Strummer’s sonic omnivorousness, his music existing in the post-dusted slipstream as a sort of stepping stone between Sublime '96 and Gorillaz 2001.

In fact, “Gamma Ray” sounds like it could've been tucked away somewhere on the Gorillaz’s debut[20] (filling out the seemingly inevitable guest spot featuring Joe Strummer on vocals).[21] As you might expect, the spectre of Sandinista! hangs over the album's moodiest cuts, including “Shaktar Donetsk” and “Mondo Bongo” — routing it all back into the mothership — while “At The Border, Guy” even sounds like a low slung callback to “Revolution Rock”, albeit filtered through the same liquid dubwise architecture in evidence on The Clash’s monster triple-LP. Interestingly enough, this time most of the record's gentlest moments happen to be tucked away on its second side, even as they feel more of a piece with their surroundings than their counterparts had on Rock Art And The X-Ray Style. “Bummed Out City” plies the same uncanny quicksilver Stones sound as “X-Ray Style”, while “Minstrel Boy” is the closest Strummer hews to his troubadour leanings, with martial drums underpinning a relatively traditional reading of one of Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies.

One thought that only really crystallized for me in the process of putting this thing together is that for all their mix-and-match, anything goes ethos, the dusted groups tended to come in a few different strains. On one hand, you had bands like 311 and Sublime, with their punk reggae and dub obsessions, and on the other you had figures like Everlast and Beck with a timely collision of folk/country/hip hop, while groups like Cake and Soul Coughing plied a sort of Latin-infused post hip hop beatnik jazz (the way Harlem River Drive, Mandrill, and War did it back in the day). Despite their existence as fellow travelers, there wasn't as much overlap as you might expect between the three flavors, aside from a shared reaction to peak-era hip hop. So 311 didn't dabble in folk or country, while Beck never really messed with reggae and dub (even if he managed to touch on just about everything else), and Cake were always off doing their own thing. In contrast, these Mescaleros records are the one instance I can think of where the Venn diagram overlaps on all counts, such was Joe’s all-encompassing vision.[22]

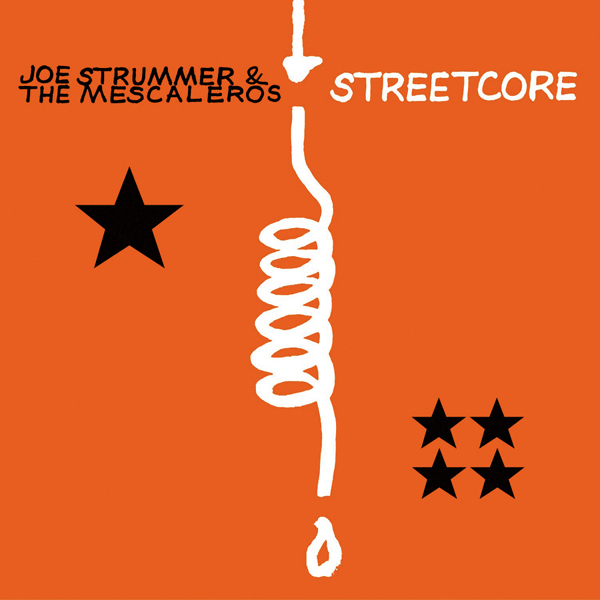

Sadly, Joe Strummer passed away in the midst of this Mescaleros renaissance, and Streetcore was put together from the sessions to serve as the band — and the man's — swansong. As such, those homespun folk leanings return stronger than ever, with “Long Shadow” almost sounding like a American-era Johnny Cash cut. In fact, Strummer had already recorded a cover of “Redemption Song” with The Man In Black that got a lot of play around the same time Streetcore was released (Cash passed almost a year after Strummer), and the album even includes its own solo Strummer version of of “Redemption Song”. There's also a healthy dose of rock 'n roll thrown into the mix, like “Arms Aloft” and the quasi-big beat moves of “All In A Day” (featuring writing input from dusted architect Danny Saber), and “Coma Girl” even got a bit of radio play at the time, but its three low-slung beatbox tunes scattered across the album that are of particular interest today.

The first is “Get Down Moses”, a phenomenal slice of punk reggae with a heavy dose of dread bass pressure and rolling surf rock undercurrents that should've been a huge hit. In fact, it probably would've been if it came out about five years earlier, in the more sympathetic climate of a year like 1997, when tunes like “Doin' Time” and “Beautiful Disaster” were filling the airwaves. As it stands, its one of the great unsung dusted moments in pop, sounding like The Wailers going head-to-head with The Chemical Brothers uptown, boasting a hard-edged, ramshackle “submarine” sound that recalls The Sabres Of Paradise’s Versus (with its collision of Depth Charge, LFO, Nightmares On Wax, and even The Chemical Brothers themselves), albeit with a stronger tune than anything on that record. And is it just me, or do those “na na, nananana na” backing vocals sound just like Mick Jones?

|

|

At the other end of the spectrum, “Burnin' Streets” is the downbeat flipside of the dusted coin. Starting out with a slow-motion beat and shades of the cosmic Stones, it gradually adds backwards guitar and even Mellotrons into its swirling soundscape before rising to its dreamy “London is burning” refrain, a tear-jerking callback to one of his old band's earliest records. One of those paradoxical Exile On Main St. is London Calling moments, it works beautifully as a sort of “Riders On The Storm” for battered old punks standing at the precipice of the 21st century, not to mention an absolutely gorgeous signing off moment for Joe Strummer.

Following swiftly on its heels, “Midnight Jam” plays something like an instrumental coda to “Burnin' Streets”, retaining a similar beat and general character that gradually goes off on a variation of its own (bringing to mind the one-two punch of “Holiday/Harmony” on the Happy Mondays’ Pills 'N' Thrills And Bellyaches). Evoking a dream late night radio session — complete with spoken radio announcements from the selector Joe Strummer — it gradually submerges into a dubbed-out piano and Mellotron-drenched downbeat psychedelia that occasionally recalls Roxy Music’s “For Your Pleasure”. It's a brilliant deconstruction of song that brings Sandinista!’s reckless studio-bound approach to bear on Streetcore’s gutsy roots music, bringing it all back home again.

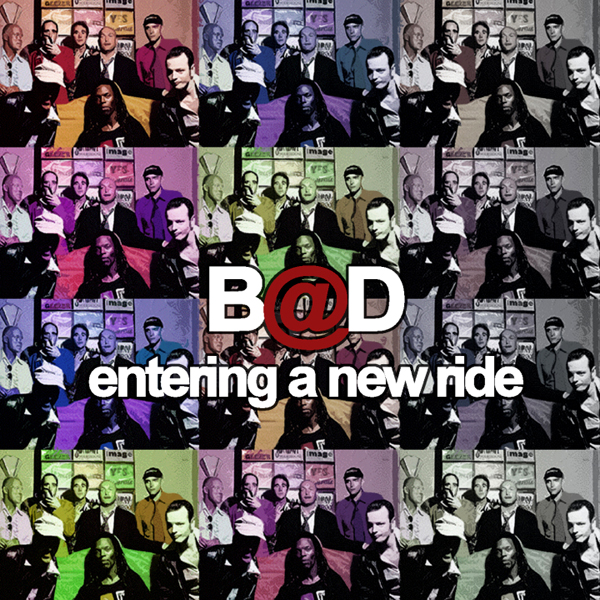

Part of what makes this all so fascinating is that Mick Jones engaged in a very similar deconstruction of his own about half a decade earlier. After a disappointing detour into punk traditionalism on F-Punk[23] (and likely reinvigorated by the process of compiling the Planet BAD: Greatest Hits retrospective), he took Big Audio Dynamite to the other extreme, retooling it as a soundsystem rather than a band, even pulling in Ranking Roger from the General Public days as an official member of the crew. This shake-up bore fruit in the shape of the awesome Entering A New Ride, which pulled in a whole array of contemporary sounds (house, techno, hip hop, jungle, dub, big beat, electro, indie dance, britpop, and so on) to deliver the quintessential 1997 album, a perfect balance of radio-ready rock and of-the-moment dancefloor punch. With everything in its right place at the right time — and with the right sound — B.A.D. were poised to recapture the wave they rode in the early-nineties with Kool-Aid and The Globe.

So naturally, the label refused to release it! Whether Radioactive balked after the under-performance of F-Punk, disliked the overall rough-hewn sound of the record,[24] or other factors came into play, only one 12" promo came out of the sessions at the time. Which is a shame. A real shame. This record would've fit in beautifully with the currents of 1997 and its collision of guitar bands and dance music (this the era of U2’s Pop, Garbage’s Version 2.0, and Primal Scream’s Vanishing Point), not to mention big beat's concurrent radio assault in the shape of The Chemical Brothers, Fatboy Slim,[25] and The Crystal Method. That's not even getting into the prevailing influence of all things dusted, with many of the big 1996 albums like Beck’s Odelay, Cake’s Fashion Nugget, and Sublime’s self-titled swansong all still generating fresh singles through the following year (with nu-metal's nascent chart dominance still waiting in the wings).

There also happened to be a rash of reliable old-timers holding it down with sizable hits on alternative radio at the time, from David Bowie’s “I'm Afraid Of Americans” (taken from the Earthling LP — heavy jungle damage in evidence throughout) and U2’s “Discotheque” to Duran Duran’s “Electric Barbarella” and Depeche Mode’s “It's No Good”, so a look-in from an old Clash renegade would've certainly been welcome too.[26] In retrospect, Radioactive should have been the perfect home for the record, having just put out the two Black Grape albums with a slew of 12" singles to match. B.A.D. had always fared better stateside than on their own native soil, and with a similar push I could see about a third of the album getting some serious radio play. Listening to something like the contemporary “Big Audio Dynamite Dub Remix” of DeeJay Punk-Roc’s “My Beatbox”, one can only imagine what the crew might have cooked up with a handful of 12" singles to work with.

As it stood, B.A.D. wound up releasing the album digitally a couple years later in 1999 (one of the first bands to do so, in fact).[27] Entering A New Ride makes a much better swansong than F-Punk, staying truer to what the band was all about as it pulled all their loose ends together in much the same way Megatop Phoenix had for the band's first incarnation. Opening with a jagged power chord blast, “Man That Is Dynamite” kicks the whole affair off with a defiant “never say die” anthem, echoing the “LIVE FAST. LIVE FAST.” inscription on F-Punk’s inner sleeve. After a couple albums that found the group sounding relatively weary, here they sound reinvigorated and firing on all cylinders. For all the dancefloor moves in evidence throughout, this is still undeniably a rock record. In fact, it might be the best place to hear Mick Jones really cut loose on guitar alongside Nick Hawkins, with gorgeous solos and heavier riffing than anything he'd done since the glory days of The Clash.

Take “Sunday Best” — which was the one track to get an actual 12" promo release at the time — with its “London town, London town” refrain repeated over screaming sirens, heavy riffing, a dread bassline, and breakbeats that sound like they were recorded in the garage around the way. Like I was just saying, a little bit of effort getting this on American radio and it would've slipped right in there alongside The Chemical Brothers’ “Setting Sun” and Orbital’s “The Box”. Even more tantalizing is “Must Be The Music”, a phenomenal cover version of Secret Weapon’s Prelude twilight-era disco classic, taking the tune into post-Madchester territory with Mick’s angelic guitar and loose, rolling breaks offset by synth squiggles straight out of Jellybean Benitez’s Funhouse playbook, recalling all those tunes on Megatop that keyed into contemporary Paisley Park. There's something about this version that's always struck me as very special, the fragility of Mick’s vocal rendering it all the more affecting (not unlike how Bernard Sumner’s came off in New Order), while the tune cloaks him in a Balearic haze like some half-remembered sunset awakening from a dream.

Quite a few tunes breach rock territory — with ten times the lust for life in evidence on F-Punk, ironically enough[28] — returning to the sort of “group chant” choruses found in early B.A.D. singles like “C'mon Every Beatbox” and “The Bottom Line”. “On The One's And Two's” and “Taking You To Another Dimension” are the perfect example of this, where the chorus is treated almost like a mantra, repeated again and again over surf rock-style breaks that bring to mind Fatboy Slim’s “The Rockafeller Skank” (from the following year). Certain catchphrases crop up throughout the record, with the chorus of one song woven into the bridge of another, while vocal snatches might crop up as samples in a third. “Cozy Ten Minutes” even starts out as a relatively straight up rock rave up before slipping into a chintzy electropop mid-section that recalls early Depeche Mode (circa Speak & Spell) or even Kraftwerk and Cluster pitched up to '45 on the decks,[29] while the roaring big beat roller “Get High” treads remarkably similar territory as Prodigy’s The Fat Of The Land,[30] where the lyrics are almost like slogans trading off over overdriven riffing and rolling breaks, rather than any sort of traditional rock lyric.

Still, this is rock 'n roll deconstructed through the machinery of a soundsystem, and there's plenty of songs that get into off-kilter dancefloor territory as wild as anything since The Globe/Megatop days. The throbbing low-slung house of “Sound Of The B.A.D.” is one such example, with a riff that recalls “The Globe” and a beat lifted from “Train In Vain”,[31] it almost has the feel of an INXS club mix until that loping bassline comes into the picture, sounding just like something from an old Mr. Fingers record. Even better is “Bang Ice Geezer”, with ten ton breaks crashing like tower blocks beneath clockwork percussion and disembodied dub (think “Radio Babylon”). Snatches of brass echo off in the distance like Eddie Palmieri’s “Caminando” as storybook chimes are dubbed-out and sucked into the ether, 101 Strings collapsing into vocal cutups snatched from their surroundings.

To top it all off, the album closes with the easy-going good time skank of “Nice And Easy”. Picking up where the Planet BAD version of “Harrow Road” left off — with its top-heavy rocksteady skank and the first appearance of Ranking Roger on a B.A.D. track — it's the record's most dusted moment by far. Kicking off with a vocal loop (“doin' it nice and easy”) that disintegrates into a pristine rocksteady bassline, its rhythm begins to take shape before unfussy breaks enter the fray with what sounds like the whole crew pitching in on vocals. The one constant is the MC (Joe Attard) guiding you through the track and interjecting his asides as time is traded between the crew's group chants, toasting from Ranking Roger, and Jones’ ethereal refrain. Mick’s guitar actually lies low for most of the song, teasing in and out of the mix before exploding into another one of those gorgeous solos in the crescendo, offering the perfect encapsulation of how that year felt at the time.

I'm gonna go out on a limb here and claim that if this song had been released as a single and circulated halfway decently, I can see no way it would have failed to be a monster hit in 1997, 1998, or even 1999. After all, this was the era when tunes like Len’s “Steal My Sunshine”, Citizen King’s “Better Days”, and Fatboy Slim’s “Praise You” could be massive hits and Sugar Ray were an honest to goodness pop phenomenon. I just can't shake the feeling that this would have been the big one, a hit on the level of “Rush” clocked in at the other end of the decade. As it stands, it's the perfect ending to an album that pulls together so many disparate strands of contemporary pop music and filters them through the sensibility of a soundsystem, all shot through with an undimmed survivor's spirit that recalls The Clash at their most ragged, rough, and carefree.

All of which sounds an awful lot like the m.o. of Streetcore, which also sounds an awful lot like what the The Clash were up to circa Sandinista!. If Entering A New Ride turned out to be a stronger swansong than F-Punk, then pairing it with Streetcore makes for a better signing off moment from Joe and Mick than The Clash’s Combat Rock, offering up a winning culmination of blueprints laid out in Sandinista! some twenty years on. Upon reflection, it's not only what they'd been up to ever since their triple threat, but something that goes all the way back to “Police & Thieves” on the debut. I mean, what is “The Guns Of Brixton” if not the square root of the Gorillaz’s “Clint Eastwood”?[32] Don't forget that M.I.A. rode a slice of “Straight To Hell” into the charts with “Paper Planes” in 2007 (by now fifteen years ago, perhaps, but in the grinding slowdown of the 21st century, it's not as long as it sounds).[33]

And that's just one strand of the tapestry, the dust on the machine, so to speak. There's also the punk disco angle of “The Magnificent Seven” to consider, not to mention “Silicone On Sapphire”’s strange automat beats, to name just a couple examples. We could even talk about Terminal Vibration, but that's a whole other story. I think there's still so many possibilities to be explored in this particular corner of the wider universe of sound, a by now neglected corner that lends itself to the overall tenor of the 21st century so far (or perhaps even as a potential antidote therein). I've often said I tend to like my pop landscape with a bit of War, a bit of Mandrill, a bit of Harlem River Drive thrown into the mix, if you will, and when everything gets too locked down and claustrophobic, I tend to lose interest. And with music as shiny and metallic as its ever been, I think a little bit of dust would go a long way. Spice up the soundscape with all the music that isn't fit for the disco, dedicated to those long lost souls dancing on the edge of forever.

Footnotes |

|

|---|---|

|

Unfortunately, this sound didn't make it to the actual record, which was awash in a flurry of mid-decade post-production missteps thrust upon the band after the sessions had already ended. |

|

|

This just months after hooking up with ex-English Beat frontmen Dave Wakeling and Ranking Roger to play guitar on the debut album (...All The Rage) for their new project, General Public. |

|

|

In fact, there was an almost comical wealth of talent to be found behind the boards during these sessions, including drum programming and remix work from rising hip hop luminary Sam Sever, freestyle king Chep Nuñez on the edit, and engineering by dubmaster Paul "Groucho" Smykle. You'll even find a pre-solo stardom Neneh Cherry (fresh from her stint in Float Up CP) featured as a dancer in the “C'mon Every Beatbox” music video! |

|

|

I've always wondered whether the song “BAD” was inspired in part by General Public’s “General Public”, which served a similar function as an eponymous album-closing hype track on ...All The Rage. Truth be told, “Sightsee M.C.!” bears an even closer resemblance to “General Public”’s dread downbeat chorus and overall overcast aura. |

|

|

I've grown to think this was an underrated aspect not just of Big Audio Dynamite but Mick Jones’ frontmanship in general. There's a whole thread of the band's music that — whether by necessity or design — finds Mick delivering his words in a half-sung/half-rapped manner that mirrors Jamaica’s “singjay” tradition. Whether it was down to Jones’ time soaking up hip hop mixtapes in N.Y., some latent Dylan influence bleeding through, or even a simple knock-on effect of working within the limitations of his pipes, there's no denying that tunes like “Sudden Impact!” and “Hollywood Boulevard” feature the same compression of language that one finds in early hip hop (and this a full half-decade before The Globe!). |

|

|

Why “Another One Rides The Bus” wasn't included on the otherwise essential remix/b-side round up The Lost Treasure Of Big Audio Dynamite is one of those mysteries of life that I'll never understand... |

|

|

Which took place at Electric Lady Studios, interestingly enough. |

|

|

There's one other (possibly even more) unsung exception to the rule, but I'm going to keep them in my back pocket for now, since they've got their own feature waiting in the wings. Besides, they almost always tended to relegate their tastiest dancefloor action to remixes and b-sides tucked away on their 12" singles (with one or two notable exceptions). |

|

|

With 2-step the flashing neon exception to the rule. |

|

|

Both albums were released less than a year apart and share many of the same tracks, which appear in different versions on each. |

|

|

The track “I Don't Know” illustrates this point perfectly, with its otherwise power pop songcraft riding a makeshift breakbeat rhythm over proto-junglist bleeps and a subterranean bassline, sounding like some strange possible precursor to what rock bands might have sounded like in 1997 if they'd been aware of speed garage and 2-step (everyone on the outside still catching up with drum 'n bass at that point). |

|

|

No joke, you could drop it into the middle of the genre-defining Headz compilation and no one would bat an eye, as it fits in so snugly with tunes like Nightmares On Wax’s “Stars” and Tranquility Bass’ “They Came In Peace” that you almost wonder why James Lavelle didn't ring up Mick for the instrumental and put it on there in the first place! |

|

|

Also check out the coda to “Innocent Child”... Moby was scraping the lower reaches of the pop charts with similar instrumentals — give or take an old blues sample laid over the top — by decade's end! |

|

|

Although I've often wondered whether the “The Globe (Studio 54 Mix)”, tucked away on The Lost Treasure Of Big Audio Dynamite, wasn't actually the original version, so perfectly do the vocals lock in with its central groove. |

|

|

Setting aside the fact that my favorite track from Guero shares its title with Strummer’s 1989 album Earthquake Weather, which may or may not be a coincidence. |

|

|

In fact, it's always reminded me of Horace Andy’s “Doldrums” (produced by 3D of Massive Attack), one of my favorite songs of that year. |

|

|

In fact, I'd be willing to bet that The Clash had a profound influence on all three of those bands. |

|

|

Which always makes me flash on Roland Orzabal’s “Hypnoculture”, sounding for all the world like a lost cut from System 7’s debut album. |

|

|

Not to mention steel-string guitar from household icon BJ Cole, who also appeared on “Tony Adams”. |

|

|

Interesting to note that Gorillaz and Global A Go-Go came out within a month of each other, during the summer of 2001. |

|

|

Maybe even more tantalizing is the fact that it sounds just like something off The Good, The Bad & The Queen’s debut — featuring Damon Albarn and former Clash bassist Paul Simonon — which at that point was still five years in the future. |

|

|

This goes all the way back to The Clash days, when they got Mikey Dread to dub tracks on Sandinista! and even roped in Joe Ely, Futura 2000, and Allen Ginsberg to appear on Combat Rock. |

|

|

However, you won't hear me utter one negative word about the oft-maligned Higher Power, the 1994 album B.A.D. released between The Globe and F-Punk. I didn't touch on it here because I want to dive into it later with an album feature of its own someday. |

|

|

Comparable in spirit more with The Fall’s rough-and-tumble 1997 outing Levitate, for instance, rather than the big budget, cinematic sweep of U2’s Pop. |

|

|

Norman Cook even nicked B.A.D.’s breakbeats + "I Can't Explain" equation a year earlier with Fatboy Slim’s “Going Out Of My Head”, snagging a sizable hit in the process. Incidentally, his review of the Sunday Best (12" Single) was also included with the 12" promo, where he reminds listeners that “this is the man who in The Clash introduced a generation of NME readers to rap, funk and reggae.” |

|

|

I can say with absolute certainty that I would have LOVED this album in 1997. |

|

|

I only got to hear it a couple years after that, but once I did, I had it on repeat for the rest of the year. |

|

|

Don't get me wrong, as much it might sound like I'm bashing it here, I do enjoy F-Punk. I just think it suffers by comparison with the music that came before and after, its primary flaw being that it's meant to be a back-to-basics, Cut The Crap (heh) rock 'n roll album...but everyone sounds tired. Even so, there are a couple folky detours in the vein of “Innocent Child” that fit better with the record's overall downcast mood (and even overlap nicely with those rootsy Mescaleros ballads), and the one exception to the rock 'n roll rule: the oddball junglism experiment “It's A Jungle Out There”. |

|

|

More to the point, it prefigures the sort of 21st century “Europe Endless”-inspired pastiches found on Death In Vegas’ Satan's Circus, Solvent’s Apples & Synthesizers, and Andrew Weatherall’s swansong Qualia. |

|

|

Maybe “Get High” doesn't have quite the same sense of claustrophobic dread as a tune like “Firestarter” or “Breathe”, but the core materials are remarkably similar. To put it in terms of a crude punk metaphor, The Prodigy are to the Sex Pistols as B.A.D. are to, well, The Clash. |

|

|

This only a couple years after Garbage sampled “Train In Vain” for “Stupid Girl” (Jones likely thinking, “hmmm... not a bad idea!”). |

|

|

And I always thought “Cool Confusion” sounded just like something by the Gorillaz 25 years later. |

|

|

Despite breathless comparisons at the time to grime and funk carioca, I always read M.I.A. as the next chapter in the U.K. beatbox saga stretching back to Renegade Soundwave and beyond. |

|